Grand Canyon

The sun had fallen behind the trees fronting the black road and would strike the corner of the canyon very soon. The ruins we sought were not along the precipice, but five minutes inland along the road. It was practically between two rolling vehicles that we saw the ruins at all, but their cartoonish presentation paced our available wits. Set behind some cabins and adolescent pines, a clearing corralled the pueblo remains in short, even and complete arrangements of stone, defining chambers consecutively forming an "L," with a small stone ring beyond the long leg. They rose to half-a-shin’s height, assembled with a good deal of mortar between the coarse yellow stones. The pueblo was small, with perhaps twelve rooms, none of which longer than my body. I couldn't imagine lying down in one comfortably. All the rooms were solidly surrounded with no gaps for doors.

The kiva was small as well, framing a low, solid bench and suggesting a very intimate chamber. The sipapu was preserved, pointing away from the pueblo. There was no discernable orientation to the Canyon.

At one point you could see through the trees toward the distant sacred mountain, according to a sign, but I couldn't see it. This view—to the southeast—corresponded with the opening in the plaza.

We finished our tour and hurried back to the parking lot, practically leaping into the vehicles to find the sunset, which would touch slightly left of the hazy blue corner. In the last moments, below all clouds, the orb burst a cool heat on the faces of all its entranced observers. Color concentrated in the canyon to golden strips along the rustrubble demi-hills. You could hear night's curtain drawing behind us. Finally, the sun buried itself in the rift, sucking with it the light and life of day and leaving us alone to find a place to sleep.

Old Oraibi

Following a long and broken talk with the old curator, we drove to the village. It certainly felt as though we had no place being there and our approach was slow and self-conscious. But the curator had directed us a visitor center. Spring was not a tourist season due to the winds, but we had not experienced any discomfort. (In fact the weather was very mild, sunny with only a slight breeze.)

The visitor center was more of a gift shop, in a new solitary building before the village. It was made to look authentic, with brown stucco walls beneath protruding wood beams. The interior however had glass cases of kachina dolls beneath a suspended panel ceiling and recessed fluorescent lights. The man behind the counter forbade us from approaching the church at the end of town.

Outside the shop were two children—a boy sitting on the stairs and a girl with a basket of foil-wrapped piki bread. Two were purchased and shared amongst the group. The bread was the shape and size of a burrito, but light, flakey and oily. Bits kept sticking to my upper lip. We had no further human encounters there.

The village presented a stoic earthen labyrinth, winding along tread-pressed roads between dark breathing apertures, shut wooden doors and walls in varying stages of deterioration and reclamation. The azure sky dipped into our attention, spreading wide in the plazas where it contended with the kiva ladders.

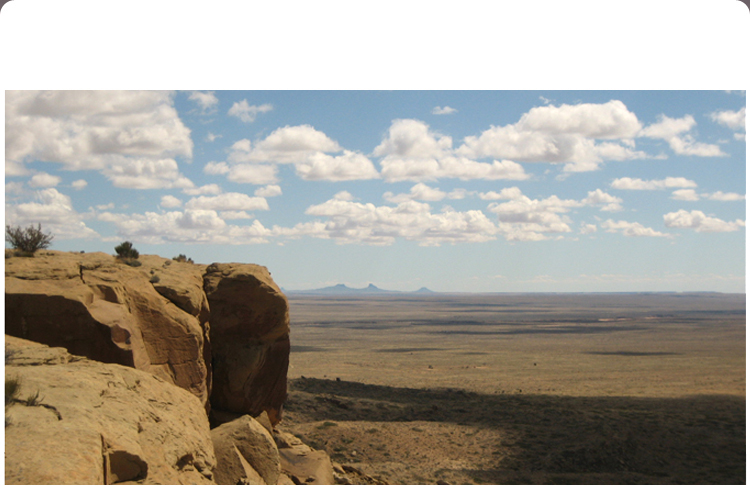

The ground stepped downward toward the end of the mesa where suddenly the walls stopped and a panorama opened the entire valley stretching away for miles to terminate at a dutiful mountain ridge huddled against the horizon.

An abandoned, crumbling building stood alone toward the edge of the mesa. It struck an austere impression—proud despite its rooflessness and crippled bell tower. The afternoon sun struck an interior wall and the three tall windows glowed pumpkin. We stood and looked at it like some rare animal before continuing back to the village.

First Mesa

The road turned abruptly at the base of the mesa and scaled the side of it at the angle of a doorstop. We met a huddled couple walking down along the precipice. The man flagged us and Brian braked, rolling his window down. The dust settled and the man crunched over to the truck. He wore a long jacket and a wide-brimmed hat; the woman didn't move from where she had stopped. The man greeted us and told us Walpi was closed due to a children's ceremony in the kiva, however we could park in Sichomovi and walk around. He said Sichomovi wasn't a Hopi town. It was inhabited by the Tewa under special conditions of protection. He drew a doll from his jacket and said it was an authentic kachina doll that he would sell to us for twenty dollars. We agreed we didn't want one and thanked him. He asked us for a cigarette and Brian gave him one of the Bali-Hais. Thus went our encounter with the kachina merchant.

Sichomovi

Dead souls of dust rise from the chest of a compact plaza—a coverless room framed by earth, bisected by a single-lane dirt road, a glowing yellow square and a glowing blue square. The road unrolls along the mesa circling wherever the end was and returning to just before our plaza: the path of the eye of a needle. Caked Mercurys and white pickups pass occasionally and we see them come the other way a few moments later through spaces in the buildings. The brown square faces within smile white, and a few arms wave. Why would these people be friendly to a couple of white guys throwing rocks in their parking lot?

The puddles were shallow, brown and uninteresting. Rob and I redirect our attention to hitting a styrofoam cup. It’s hard—after a few grabs, your area runs out of throwable rocks and you have to scoot along the bumper away from the cup. I didn't want to follow the group into the slushie shop to talk to a war veteran. I don't know why Rob didn't go in but he’s good company in our masochistic time-wasting. We throw rocks at the cup until the sun moves. The sun and the rising dust and lurching vehicles and the slung rocks and only these things moving in our universe for as long as it exists. The cup never moves.

The mesa takes a new axis to the late afternoon and the lee side accepts direct light. The cliff is shallow and rocky and it is here in the rubble children are heaving stones toward the hazy plain.

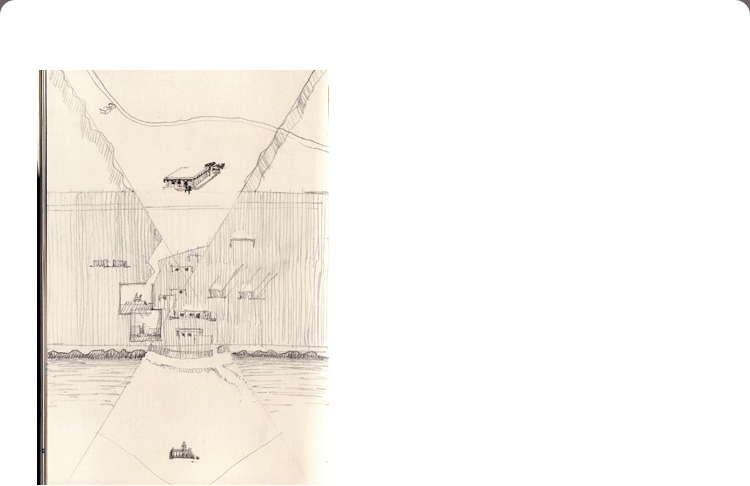

Wupatki

Swinging around the volcano past the old lava floes, we descended quickly through three distinct tree forests--aspen, ponderosa, and pinyon--the trees progressively thinning until there were only shrubs and red soil. We descended until there was nothing left of the volcano but its red knuckles, tugging the edges of the high desert. Here amidst the cliff-folds stood a large, tall adobe structure, the symbolic remains of a far-ranging node for the trade of goods, crafts, and culture beneath the shadow of Sunset and the sacred mountain: Wupatki, abandoned since before the volcano's last explosion some 250 years ago. There was no indication of the fertility of the land needed to support such a large community. The isolated village-building was built upon/of the red rock, its back to the setting sun. The large, exposed chambers exhibited an ingenious fireplace vent. There were some preserved enclosed chambers, small in themsleves but accessed through very narrow and high passages that drew you right into the clifface before turning you left or right at which time you realized the cliff face was one of the four walls in the room. Further downhill there was a ballcourt, a unique feature for this region and likely an import from Mesoamerica. The court was a simple oval-shaped depression of even clay earth with two entrances on either of the long ends. These entrances were framed in stone steps down and narrow enough i could easily place my hands on either wall. The court was defined by chest-high stone retaining walls.

A little aside was the blowhole-a material source of the breathing land, dilivering a constant and strong gust of cool air. It wouldn't take water. We spent most of our visit here.

By the end there wasn't enough light for pictures. no direct sun, though the sky was clear and the surround glowed from the sky's ambient light. It would be dark by the time we found a place to camp.

Sacred mountain

By the time we started looking for campsites that final night, darkness had already fallen. I was frustrated and tired and tried to nap in the back of the truck through what turned out to be a dramatic and frightening search. I could hear the wind rushing up and past the cab on the other side of the steel panel. We must have stopped three times and each time it was a worse prospect. Once the doors opened and Brian and Rob got out and left the doors open and the wind just whistled and howled. I learned later that the few trees at these places were crooked, the ground just covered with volcanic rock, and that the girls wouldn't get out of the van. I simply wished they'd close the door because a draft was coming in under my coat at the shoulders. Finally the decision was made abandon Sunset Crater, drive back to the highway, cross it, and search for sites in the 'Forest there, closer to the foot of the sacred mountain.

Here there were several cars already but a spot as well. After setting up camp and adjusting to the night we discovered our camp sat at the edge of a meadow at the foot of a wooded ridge. A team of us stalked out into the trees to find firewood which was abundant pine debris and even a whole fallen tree to harvest from. After starting the fire and eating dinner we began to relax and goof around. The stars came out and defined the silhouettes of the mountains around us, mostly to the west. The sacred peak was up there, not too far from us, embraced by the night sky.

The circumference of the camplight tighted and we decided to get some more wood, to embark on a mission for more wood, to climb the ridge in search of some great campfire wood. The boys got excited and rounded up flashlights. The girls opted to stay at the fire.

The massive finger drew us in, a breath of the land sucking us along, the needle-covered slope grasping our hands and pulling our ankles, positing us briefly on an intermitant and cleared ledge before drawing us anew, led by our distancing breath. Soon all air seemed to taunt, to dance just out of reach, upslope, at the end whereever it was. Jake embraced a dead tree, declaring accomplishment--ironic in a way because or goal had now changed. or perhaps we had simply forgotten it as the needs of warmth recently took priority. But we were warm now, or had ceased to be cold, and dissatisfaction became only a destination, and we dared not tempt the sirines of pity.

Far below, the glowing chamber of the fire was pinwheeled by four stripes of darkness--the girls were dancing. I found on the ledge upon which we rested a surveying stake and deemed it fit for sacrifice. Rob came back with a peculiar stick that branched abruptly and oppositely, resembling a yoke and adopting same title. Jake pulled up behind with the dead tree--the companion tree. Brian and Gabe had carried on up the mountain. Jake dropped his tree on the grassy ledge and we followed.

We were approaching the ridge. Ahead through the pine trunks I could see the glowing rim of the night sky. This propelled me faster. Brisk air filled my hot lungs as I clawed the ground and cruched my wincing legs. Brian and Gabe had stopped right there on the hill.

"Did you see that?" Gabe was whispering.

"What?"

"There was a bird right there. A giant. I swear it was three feet tall and looking right at me." He was awestruck. "Did you see it Brian?"

"Yeah." Brian was spooked.

"Where'd it go?"

"It kinda took two steps and vanished. I was a peaceful spirit--a turkey kachina of the mountain."

Then Gabe pulled a big red balloon out of his sock, blew it full and floated off into the stratosphere.

The slope leveled off into the final clearing of the ridge. The ridge was traced by the wide cleared path of a fire road, which snaked on up toward the sacred mountain which sat like a king amidst its court of scarcely-smaller mountains. The stars twinkled. The air was still. Gabe pointed out some strange distortion in the sky. He said it looked like a giant bear had clawed the heavens and he was right. Nothing made a sound. We couldn't see the camp anymore. And commanding the sky was the silhouette of the foreboding sacred mountain. On the ridge were a number of fallen trees, fallen all in the same direction, away from the mountain. We wandered up the road. Before too long we came across a large upright and very dead tree, whose sickly gnarled branches embraced the landforms behind it. At its foot the earth was grassless and dead, conintuing that way into an avenue of death fading into blackness. No one crossed that line. Jake decided not to take one of the fallen trees as firewood. We wantered back to Jake's Companion which he decided to leave on the mountain, walking now along the fallen trees to solemnly descend the ridge.